Understanding how we move towards the future of evidence generation.

Over the past few months, the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS") published two comment opportunities and a request for information (“RFI), respectively, related to health technology infrastructure. FDA’s comment opportunities specifically related to (1) adopting Dataset-JavaScript Object Notation (“Dataset-JSON”) as an exchange standard for submitting electronic study data to FDA (our submission can be read in full here) and (2) the benefits of adopting Health Level Seven (“HL7”) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (“FHIR”) to improve real-world data ("RWD") submission to FDA (our submission can be read in full here). CMS published an RFI that contained a wide range of questions related to improving and advancing the health technology ecosystem (our submission can be read in full here). Highlander Health Institute (“HHI” or the “Institute”) welcomed the opportunity to provide its thoughts on these important topics. Here, in Part 1 of our “Mosaic Medicine” of blog posts, we will recap some of the themes from our submissions.

As we move toward a more interoperable national healthcare infrastructure, it is important to adopt standards and schema that enable harmonization of data from clinical investigations and data derived from real-world sources. One of Highlander Health Institute’s main theses is the importance of thinking about clinical trial data and RWD as two sides of the same coin - they are both examples of clinical data. The only difference between the two are variations in the circumstances and controls through which the data are collected. For this comment letter, we define RWD as clinically relevant data collected outside the boundaries of a formal clinical trial. Data sources include EHRs, administrative claims, -omics data, imaging data, digital pathology, and other formats. The value in considering clinical trial and RWD as differing versions of clinical data is that it provides a more holistic perspective of a patient’s health and the impact of a medical intervention. Clinical trials are typically a point-in-time snapshot that assesses whether a medical product works in a controlled environment. RWD provides information about how a medical product works in a broader context, which can include social determinants of health and other factors that may impact wellness. There are crossover scenarios such as pragmatic clinical trials and prospective registry studies which have features of clinical trials and RWD; regardless, they are manifestations of these two data sources - clinical trial data and RWD. A full picture of a patient’s health can only be painted when you leverage both data sources. Our comments across all docket submissions aimed toward achieving this unified vision of patient health and a modern data infrastructure for clinical research.

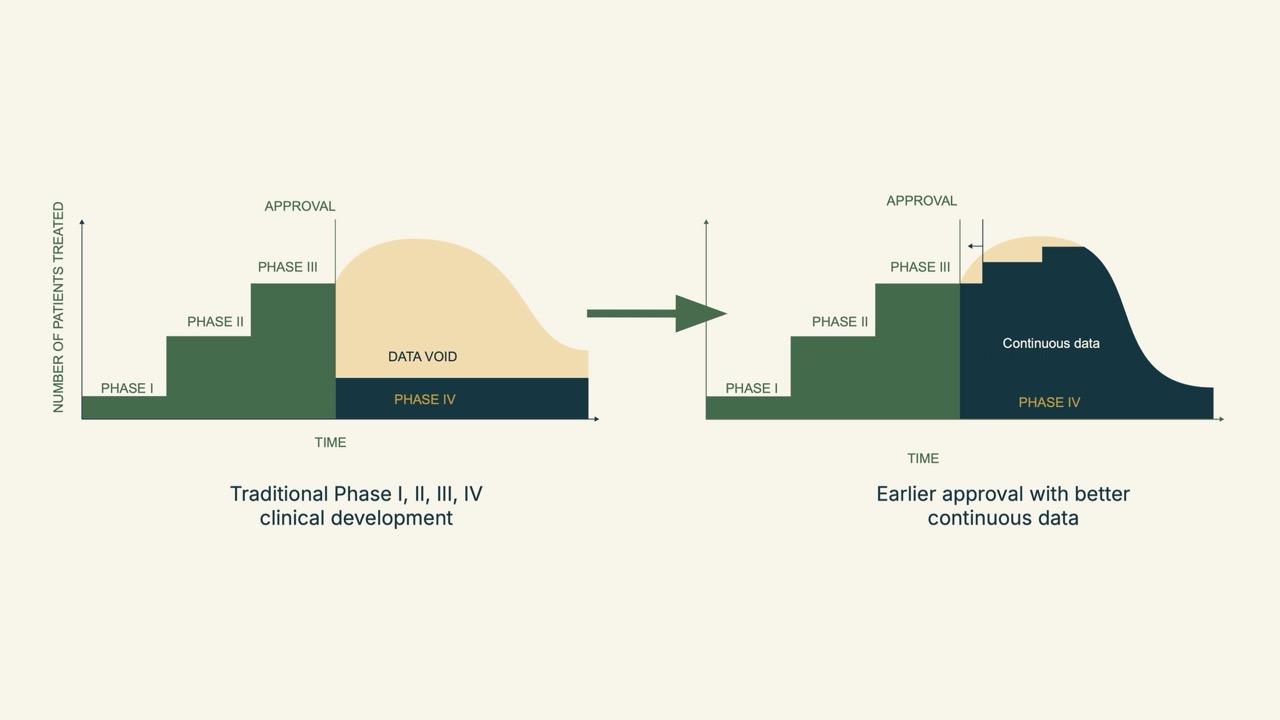

Once we embrace this change in terminology and how we view data, it becomes easier to understand the accompanying industry shift in clinical evidence generation. Clinical evidence generation is changing. For decades, we relied on formulaic phase 1 through 3 clinical trials to systematically collect, analyze, and interpret safety, efficacy and value data. Each step was distinct, with study protocols and data collection abruptly beginning and ending. The studies themselves were limited to answering pre-specified questions, and post-approval data was relatively scant.

While this approach has worked, somewhat, it has been slow, expensive, and generally inefficient. For example, it is not particularly good at determining how therapies work in different populations. In addition, there’s little cross-talk between clinical trials and day-to-day care, limiting the industry’s ability to determine how well an intervention works outside its carefully curated trial. Context is easily lost.

However, new regulatory approaches, such as accelerated drug approvals and global investments in biologics, are setting the stage for enhanced clinical evidence generation. Treatments can now be approved on a smaller, but still compelling, collection of safety and efficacy data – derived from single-arm studies or surrogate endpoints. These shifts first appeared in HIV, oncology, and rare diseases.

When we graph this shift from pre-approval to post-approval evidence gathering, it looks a lot like a snail. While data collection under the traditional phase 1 through 4 approach shows a steep drop-off after phase 3, the emerging approach provides continuous collection, which is better for patients and populations.

We look forward to talking more about “The Snail” in our second blog post in the “Mosaic Medicine” series.

Mosaic Medicine

Institute | Resources

Public Policy

Technology